RACCOON HISTORY - UNITED STATES

PRE - COLONIZATION ERA OF THE RACCOON

In North America, Native Americans regularly hunted raccoons as food and for their fur, which they used to make clothing. Fur from various mammals, including raccoons, was used by certain indigenous people to create hats. The size of the pelt and the thickness of the fur made raccoon pelts an attractive choice for hat-making. The raccoon’s tail, often left attached to a pelt, became a prominent component of these caps. In addition to being part of one’s normal hunting attire and a means to stay warm in the winter, possession of a “coonskin cap” sometimes conveyed special status within a tribe.

Native Americans used more traditional trapping methods, such as basic snares, pit traps, and deadfalls. In the early 16th century, European settlers brought metal trapping devices with them and established the North American fur trade with Europe. The fur trade was the main source of commerce for settlers and funded the extended period of colonization.

COLONIZATION ERA OF THE RACCOON

Around 1550, the "Beaver Era" started and would last for about 300 years. The beaver population at the time was prosperous and widespread throughout almost all of New York State. Pelts were treasured for their warmth, texture, and durability, so many were traded, sold, or used in clothing production. Other furbearers were trapped during "The Beaver Era," including the bobcat, badger, muskrat, RACCOON, river otter and coyote.

Early colonial settlers used raccoons as a source of fur and meat during the 1600s, a practice that continued through the 1800s. Raccoon fat was used as a lubricant, leather softener, and replacement for beef lard. Although raccoon pelts were not as prized as those from beaver, they still became objects for trade and bartering in poorer rural areas. As was true for Native Americans, settlers also made coonskin caps, which became an iconic image of frontiersmen like Davy Crockett and Daniel Boone.

Early settlers also brought the European tradition of hound hunting to the New World in the 1600s, where hunting success was enhanced by relying on the dogs’ keen senses of sight and smell. Since raccoons first appeared in written records in 1612.

FRENCH FUR TRADE OF THE RACCOON

The 1600’s - France’s claim to Canada and neighboring areas dates back to 1535 when Jacques Cartier discovered the St. Lawrence River and sailed to the site of what is now Montreal. In 1608 Samuel de Champlain arrived as governor, and settlement began.

Many of those first immigrants found the fur trade an easier and more profitable existence than the drudgery of farming. To control the trade, a string of outposts was established, some where missionaries had already settled. Years before Detroit was founded, several of these forts, or trading posts, were flourishing in Michigan: Sault Ste. Marie (1668), Fort de Baude at St. Ignace (1686), Fort St. Joseph – where Port Huron is now (1686), one in St. Joseph (1679), and one in Niles (1691).

Before long, Cadillac reported that 2000 Indians had set up their living quarters in the area, and others were coming in to trade their furs. The pelts that were shipped from Fort Pontchartrain of Detroit included bear, elk, dear, marten, RACCOON, mink, lynx, muskrat, opossum, wolf, fox and, of course, beaver. Within a rather short time, Detroit was established as the center of the Great Lakes fur trade.

ENGLISH FUR TRADE OF RACCOON

The 1700’s - For the next forty years the prices for goods in Detroit were quoted in terms of beavers or bucks a buck was a buckskin, the hide of one large, prime, male deer.

The British decreed that one beaver pelt was worth one good buckskin or one small buckskin and one doeskin.

One small beaver was worth one marten or two RACCOONS, while one large beaver might be worth as much as six RACCOONS

The Commandant at Detroit in 1772 described the traders as “a sad set, for they would cut each others’ throats for a raccoon skin”

HUDSON BAY COMPANY FUR TRADE OF THE RACCOON

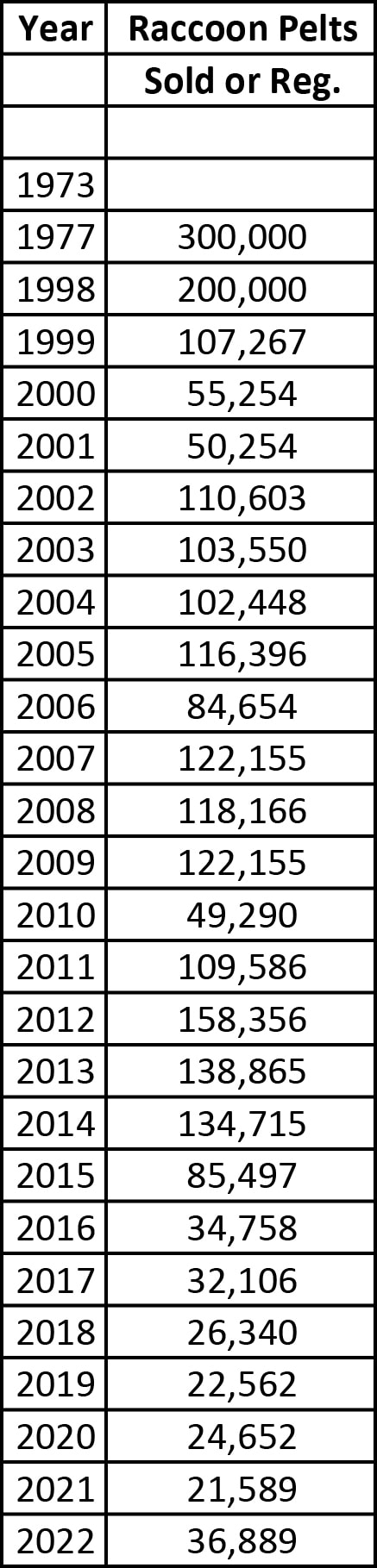

Hudson Bay Company from the 1800s and early 1900s, hunters and trappers in the U.S. sold an average of about 3,500 raccoon pelts to the Hudson Bay Company annually.

By the mid-1940s, annual national pelt sales to the Hudson Bay Company had increased to 1 million, but ultimately rose to nearly 2 million by the early 1960s.

UNITED STATES FUR TRADE OF THE RACCOON

- The Raccoon U.S. harvest averaged about 360,000 per year in the 1930s, increased to about 900,000 per year in the 1940s, and increased further to 1.3 million pelts per year in the 1960s (40 times greater than the Canadian harvest).

In the 1970s the U.S. harvest more than doubled to 3.1 million pelts, and thus far in the 1980s the harvest has averaged about 4.2 million pelts per year (26 times greater than the Canadian harvest).

The Raccoon populations, although they had declined to low levels by the 1930s, then experienced a continent-wide population explosion from 1943 to the late 1940s. Since that time, high population levels have been maintained to such an extent that the raccoon range has expanded to include areas where they were rare or absent during the 1930s.

Hence the large harvest of raccoons during the 20th century is mainly a reflection of the increase in the sizes of raccoon populations.

Additionally, in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, raccoon coats were extremely popular in the United States, especially among college students, and this popularity has continued to the present partly as a result of the moderate price of raccoon coats.

The total North American yearly average harvest of more than 4.4 million pelts in the 1980s makes the raccoon harvest the most valuable of all North American furbearers. The value of the North American harvest of raccoons was estimated to be about $94 million (CDN) in 1982–83, about 3.3 times greater than the value of the second most valuable species, the muskrat ($28 million CDN).

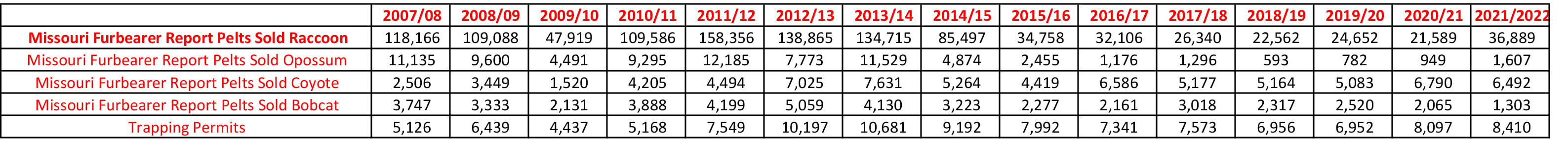

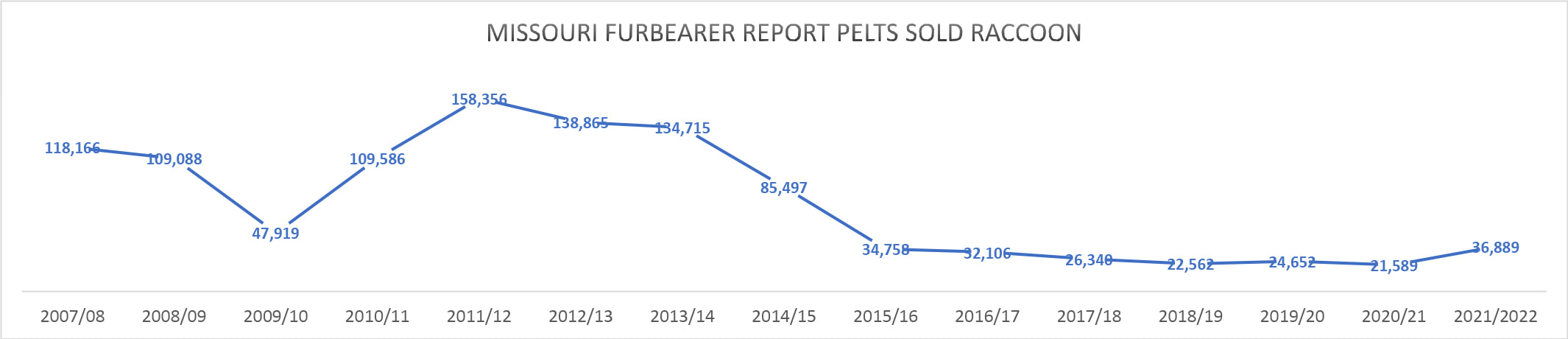

Feb 2023 - International source - The harvest of raccoon for United States fur value is the lowest it has ever been, less than 100,000 and could be far less.

The Trapper

December 2023

Latest Fur Market Insights

Raccoons remain at dismal prices until Russia comes back to table. Until war is over it won't happen.

I cannot see raccoon prices going upward for the NEXT THREE YEARS!

In the 1970s the U.S. harvest more than doubled to 3.1 million pelts, and thus far in the 1980s the harvest has averaged about 4.2 million pelts per year (26 times greater than the Canadian harvest).

The Raccoon populations, although they had declined to low levels by the 1930s, then experienced a continent-wide population explosion from 1943 to the late 1940s. Since that time, high population levels have been maintained to such an extent that the raccoon range has expanded to include areas where they were rare or absent during the 1930s.

Hence the large harvest of raccoons during the 20th century is mainly a reflection of the increase in the sizes of raccoon populations.

Additionally, in the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s, raccoon coats were extremely popular in the United States, especially among college students, and this popularity has continued to the present partly as a result of the moderate price of raccoon coats.

The total North American yearly average harvest of more than 4.4 million pelts in the 1980s makes the raccoon harvest the most valuable of all North American furbearers. The value of the North American harvest of raccoons was estimated to be about $94 million (CDN) in 1982–83, about 3.3 times greater than the value of the second most valuable species, the muskrat ($28 million CDN).

Feb 2023 - International source - The harvest of raccoon for United States fur value is the lowest it has ever been, less than 100,000 and could be far less.

The Trapper

December 2023

Latest Fur Market Insights

Raccoons remain at dismal prices until Russia comes back to table. Until war is over it won't happen.

I cannot see raccoon prices going upward for the NEXT THREE YEARS!